Friday 14 July 2023, 22:30PM

The Fallacy of Code Coverage

Having a high code coverage can lead to many symptoms, such as a sense of pride and accomplishment, a pat on the back from your manager and a false sense of security.

Here's a super quick post on code coverage, and why it can sometimes be deceiving. I'll use a dummy example in TypeScript here, but the concept at heart is true for every single language out there.

export function myFunction(a: string, b: number) {

if (a === "foo") {

return a.repeat(b);

}

return `${b} ${a}`;

}

describe("100% code coverage right here", () => {

it("can repeat 'foo' 5 times", () => {

const result = myFunction("foo", 5);

expect(result).toEqual("foofoofoofoofoo");

})

it("can do the other thing", () => {

const result = myFunction("abc", 5);

expect(result).toEqual("5 abc");

})

})

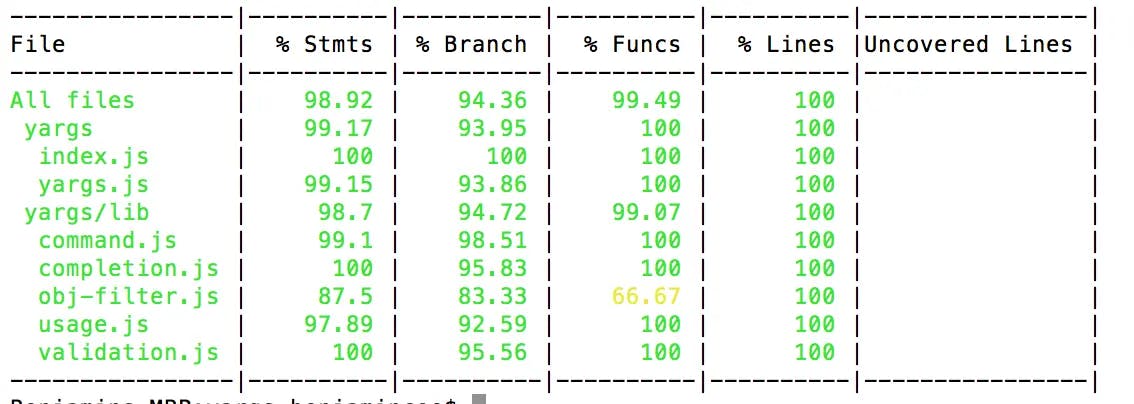

Bam, that's 100% code coverage for you. But if you've got a keen eye, you'll spot that this:

myFunction("foo", -5);

will throw an error. This example might seem a bit obvious or artificial, but that's precisely the point - it's significantly harder to spot these shortcomings of your tests when it comes to more complex, real world code. In my experience, the most common misses when it comes to high coverage tests, are:

- Null pointer errors, usually for languages that don't have strict null checks (and sometimes, for those that do as well)

- Bad array index access, most often trying to access the first element of an empty list. You could argue this one is essentially another case of the above.

- Edge cases in business logic that weren't accounted for

- Unaccounted branch coverage i.e. when you've got mutable variables being changed by various

ifstatements - maybe a bad combo could lead to one of the above.

So what's the moral?

Your code coverage is only as good as your tests. If you write tests trying to chase 100% code coverage, you'll probably be more likely to have worse coverage of actual bugs and errors. Instead, focus on writing tests that cover all your business logic cases and are likely to alert you to future breakages.

TL;DR

Low code coverage is bad. High code coverage is better, but 100% code coverage does NOT mean your code is free from errors.

Enjoyed this read? Comment and support me ❤️

If you enjoy the above article, please do leave a comment! It lets me know that people out there appreciate my content, and inspires me to write more. Of course, if you really, really enjoy it and want to go the extra mile to support me, then consider sponsoring me on GitHub or buying me a coffee!